Soliloquy

Kenneth Goldsmith specializes in writing books so long and boring and excruciatingly attentive to minutiae that no one can be expected actually to read them. Consider Day (Figures, 2003), in which Goldsmith transcribes verbatim the contents of an entire single issue of The New York Times, including marginalia, bylines, captions, and even stock prices. This 840-page tome is so mind-numbingly large and mundane that even Goldsmith has purportedly confessed that, at a certain stage, he gave up on hand-keying the text and instead scanned pages and used text-recognition software to import it.

That such books have risen beyond mere cult curiosity and become fixtures of the American literary terrain—largely without even getting read—is either a testament to their quality or a telling indication of just where their strengths lie. And let’s be clear: Goldsmith has frequently stated that he actually wants his books to go unread, to be recognized far and wide as supremely unreadable. Such are the stakes of his project.

The books of his “American Trilogy” continue such excruciating attentions to language, as it exhaustively describes and thoroughly constructs our ambient environments: The Weather (Make Now, 2005) transcribes a full year of NYC-area televised weather reports; Traffic (Make Now, 2007) transcribes NYC traffic reports; and Sports (SPD, 2008) transcribes the full broadcast of the longest baseball game on record, a five-hour 2006 bout between the Yankees and the Red Sox. Just as, in this trilogy, Goldsmith’s idea of the “American” never strays far beyond Manhattan, so has his idea of poetic invention remained quite confined to the “uncreative” processes of transcription and recording that he considers a radical departure from the implicitly conservative eddies of traditionally expressive writing. If his experiments thus miraculously help us to escape the shackles of crypto-fascist humanisms, we pay our way in boredom—and even, at times, by sacrificing the very act of reading itself. Who wants to write a new poem, a new novel, when the real space for invention lies in regurgitating the language already floating around us? And by the same token, who wants to read such regurgitated language, when we could be watching The Office instead? In the moment after my jaw drops at how clever Goldsmith really is, I find myself fighting the urge to take my ball and go home.

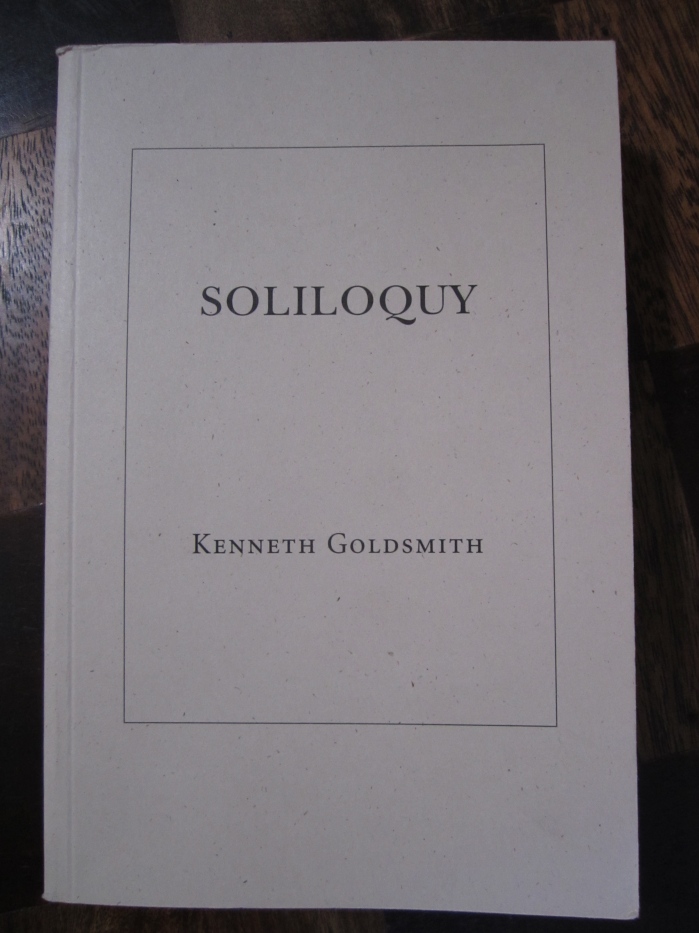

As its title suggests, Soliloquy (Granary, 2001) helps me to work through this sense, when considering Goldsmith’s work, that perhaps, as Larkin put it, “books are a load of crap.” Weighing in at 296 pages and 1.4 pounds, this volume provides a transcription of every word uttered by the author during a one-week period. He kept a voice recorder on his person during this time and subsequently transcribed the results. Take one look at the book, and you’ll see that the transcription alone must have been an heroic undertaking—though again, if we wanted a sense of just how hard great writers work, we already had Flaubert and Tolstoy (and Tolstoy’s wife, who lacked the luxury of a QWERTY keyboard when she transcribed hubby’s massive manuscripts, over and over again). These scribblers were kind enough to leave us with texts not only difficult to produce but potentially enjoyable to read. If Flaubert was a bourgeois apologist, then Goldsmith may be an apologist for not reading books at all. Works like Soliloquy overwhelm, but perhaps not intellectually. They overwhelm physically, visually. They force us to ask how we could—who possibly could—have time to read his work. And what can it mean to take a book seriously, if not to read it?

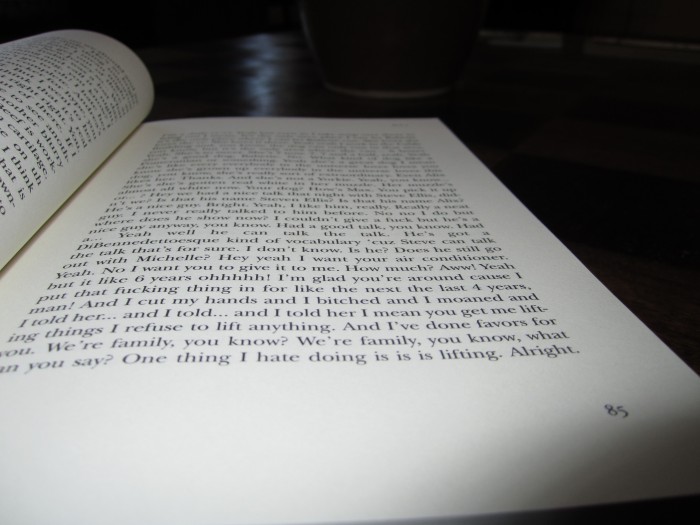

Goldsmith tells us that he transcribed the recordings of Soliloquy during eight-hour days as a writing resident at some fancy French retreat. He also tells us that Soliloquy is an “unedited document,” despite his apparently having decided not to transcribe a single word of the many interlocutors with whom he spoke during the recording process—interlocutors whose voices presumably, in some cases at least, also registered on the microphone. Far from getting the intimate sense of language’s daily textures that the project seems to promise, the book instead provides us with an extended experiment in hearing only half of a conversation. It is like that annoying experience of overhearing some stranger on the telephone—say, while you’re in the airport or on a bus.

After reading a little of this, I decided to ruin the story for myself by skipping to the end. The very last page of Soliloquy offers a Postscript, a maxim Goldsmith has often repeated elsewhere: “If every word spoken in New York City daily were somehow to materialize as a snowflake, each day there would be a blizzard.” Dear readers, this simply is not the case. There is wide variation among estimates of how many words people speak per day, but 20,000 per day is among the higher figures. Let’s generously assume that New Yorkers speak twice as much as average mortals, so that’s 40,000 words per day. Let’s look only at the island of Manhattan, the city’s most densely populated area. Even more generously, let’s take Manhattan’s daytime population rather than the number of actual residents: that’s 2.87 million people, which we’ll round to 3 million. Multiply 3 million by 40,000 words per day, and you get 120 billion words. That is, by any account, a lot of words. But what if they were snowflakes? The total land area of Manhattan—again, generously, ruling out bodies of water—is 59.5 square kilometers, which we can round to 60 square km, which is equal to 60 million square meters. A little division—120 billion over 60 million—and you get a paltry 2,000 snowflakes per square meter. Now, I can’t find figures on the average number of snowflakes per cubic centimeter—and likely that figure varies wildly—but I can confidently say that 2,000 flakes distributed over a square meter of ground is not a blizzard. That’s not even a healthy dusting. For those following at home, we’re talking about 0.2 snowflakes per square centimeter. The Postscript to Soliloquy, like the book itself and so much of Goldsmith’s other work, ultimately bespeaks a powerful attraction to the idea of great quantity but not to its actuality, for the actualities of scale in our lived worlds do not always align as interestingly with our ideas of scale as one might hope. In other words, the verbal blizzard is like Soliloquy itself: the idea of it is rather lovely. But its virtues may stop there, if we still live in a world where books are for reading—and, one hopes, for enjoying. And where the most troubling kinds of weather lately seem to be those that leave snowflakes a bit too thin on the ground.

Nazi-Deutsch/Nazi-German: An English Lexicon of the Language of the Third Reich

Maybe you are a professor of German culture. Or maybe, as a hobby, you research and reenact the major historical jargons of Europe. Or maybe you’re already thinking about this year’s Halloween costume and have considered dressing as a Nazi, so that everyone at the party can smile uncomfortably upon your entrance and then, several drinks later, finally take you aside and tell you just how far beyond the pale you have wandered this year—this, as you gaze across the room at the two smiling Maos, welcome in the fold.

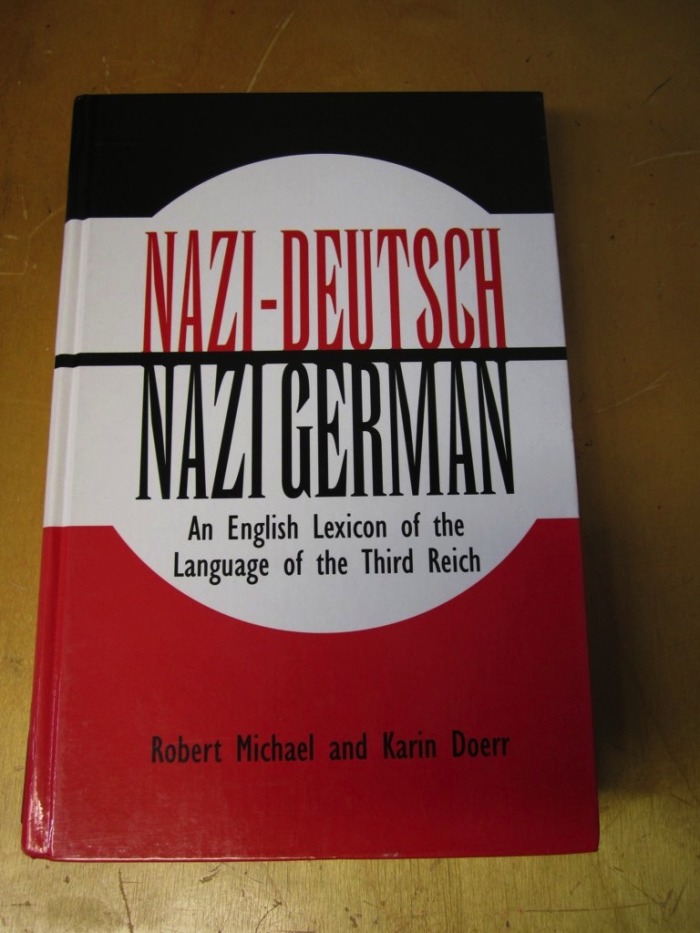

If any of the above is true, this wonderful bilingual glossary, Nazi-Deutsche/Nazi-German: An English Lexicon of the Language of the Third Reich, might be just the thing for you. Written by Robert Michael and Karin Doerr, this surprisingly manageable volume provides all you need to know about the various slang words, bureaucratic nomenclatures, and military terms of art the Nazis bandied about during their murderous rampage. It will surely help you to interpret those obscure archival documents you’ve stumbled across, or at last to make sense of those letters grandma saved from great great uncle Wilhelm, or even, come October, to make your own guttural pronouncements one measure more authentic.

Having written their reference clear through the Zs, Michael and Doerr can now, unlike most lexicographers, rest in the comfort of a task completed. Whereas most dictionaries of modern language will demand constant revision and expansion to keep abreast of changing verbiage, the language of the Nazis is more or less done with evolving. It may be fitting, then, that the authors introduce their lexicon with two definitive essays on the ideology of the jargon of the Third Reich. Their passion for the subject really comes through in the essay titles: “Nazi-Deutsch: An Ideological Language of Exclusion, Domination, and Annihilation,” by Doerr, and “The Tradition of Anti-Jewish Language,” by Michael. It should come as no surprise that the ideological gist of Nazi jargon is rather an open-and-shut case, but the authors make the assessment especially cutting and clear. As Doerr puts it at the start of her essay, “German, as it changed during the Third Reich period, represents a deviation from human and humanistic language development and a violation of civil interaction and even the meaning of speech.” The sinister black and red cladding drives home this point: Nazi language barely even qualifies as a mode of human communication. We the humanists spend plenty of time learning that language is a pure texture of ideology and difference, but few are the occasions for summing up an entire lexicon in two tidy essays. Michael and Doerr bring off their anti-Nazi pronouncements with rare verve and aplomb.

A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel

It is a thing uncommonly strange to see a book appear at the physical expense of another book, but here we have it. British artist Tom Philips published his “treated” novel, A Humument, in 1970 to much art-world fanfare and delighted chin-scratching. Philips had begun the project some years earlier, when he sauntered into a bookstore and selected “by chance” a book that he would then alter (read: enhance? mutilate? transform? plagiarize? appropriate?) to make his own work. The book Philips selected was A Human Document, a supposedly “forgotten” 1892 novel by the wonderful and multi-talented Oxford man, William Hurrell Mallock. It remains rather a mystery to me why Mallock has come in for so much rough treatment this past half-century. Perhaps it’s because his economic writings are anti-socialist in a way that, these days, has become quite more than gauche. Whatever the man’s political leanings, A Human Document seems rather a delightful novel for a rainy Sunday afternoon, well worth the read in chortles and ah-has.

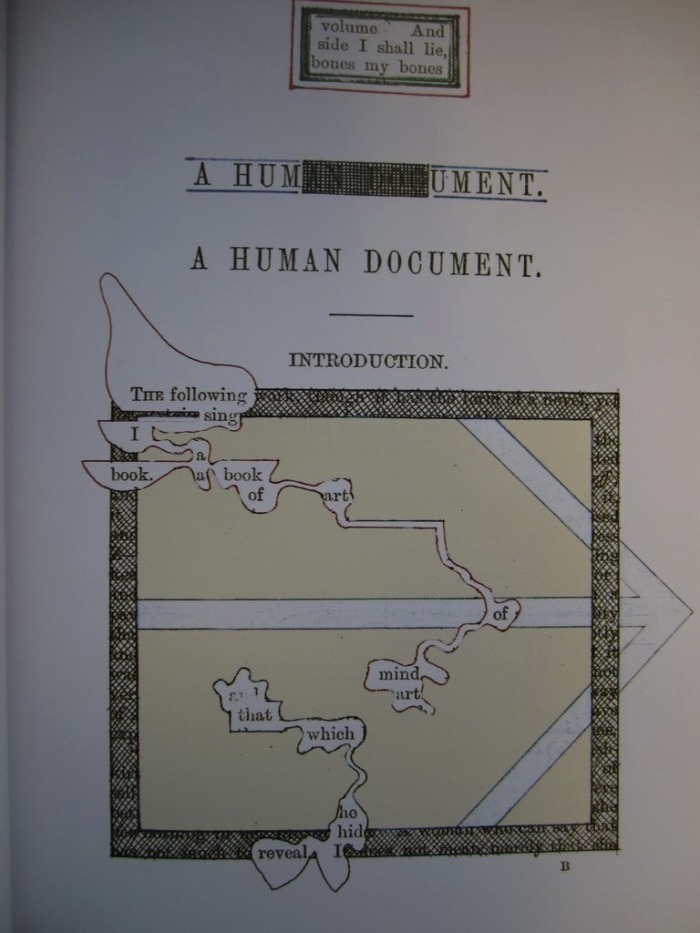

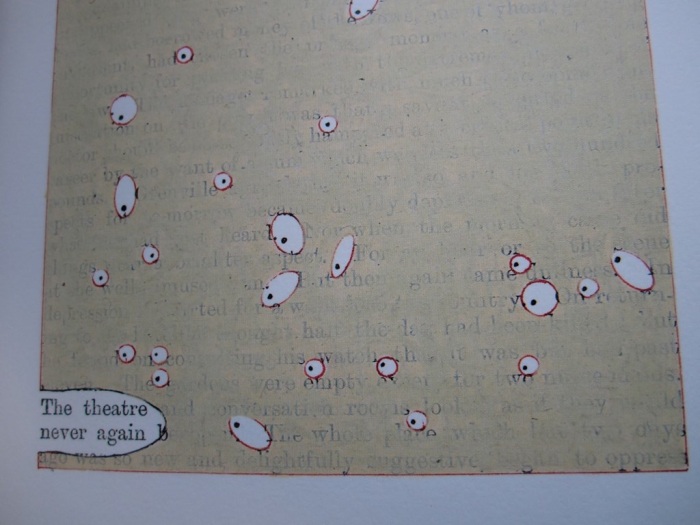

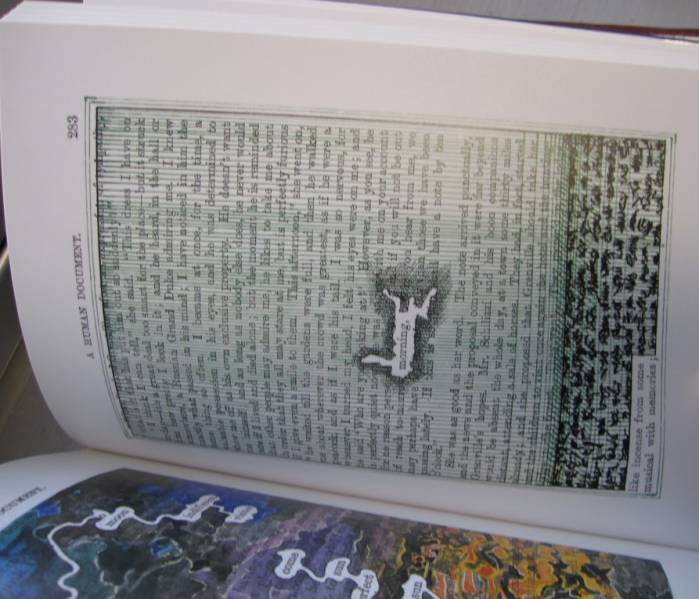

Mallock’s novel is not, in and of itself, a particularly strange book. Well, that all changed when Philips got his hands on it. As you can already see in the “treated” version of the opening page, Philips’s strategy is to make all sorts of strategic colorful doodles over Mallock’s carefully wrought verbiage, in order to construct a “new” work, the title of which emerges through partial erasure and conflation: A Human Document.

The transformed work purportedly tells the story of one Bill Toge—a character not evident in Mallock’s writing. But the true pleasure of the book, if you take it at all, lies in the stunning visual textures Philips deploys throughout. After all, we can safely suppose that had Philips wished simply to tell a story about a character he’d invented, this Bill Toge, he might have turned to blank paper and the not insignificant resources of his own imagination. But no, Philips is a visual artist, and his project for A Humument has always been primarily visual.

As someone interested in strange books—and only secondarily in, say, strange doodles—I can hardly help but wonder what it would mean to produce a “treated” version of A Humument itself. I find myself tempted to transcribe with loving care each of Mallock’s words that Philips left visible, peeking through his designs, and to typeset them in the most visually plain, regular fashion of prose that our technology can muster.

In the meantime, A Humument is available for purchase in book form, and Philips also has created a Web site for A Humument, where you can “read” the full text online and even download the iPad app.

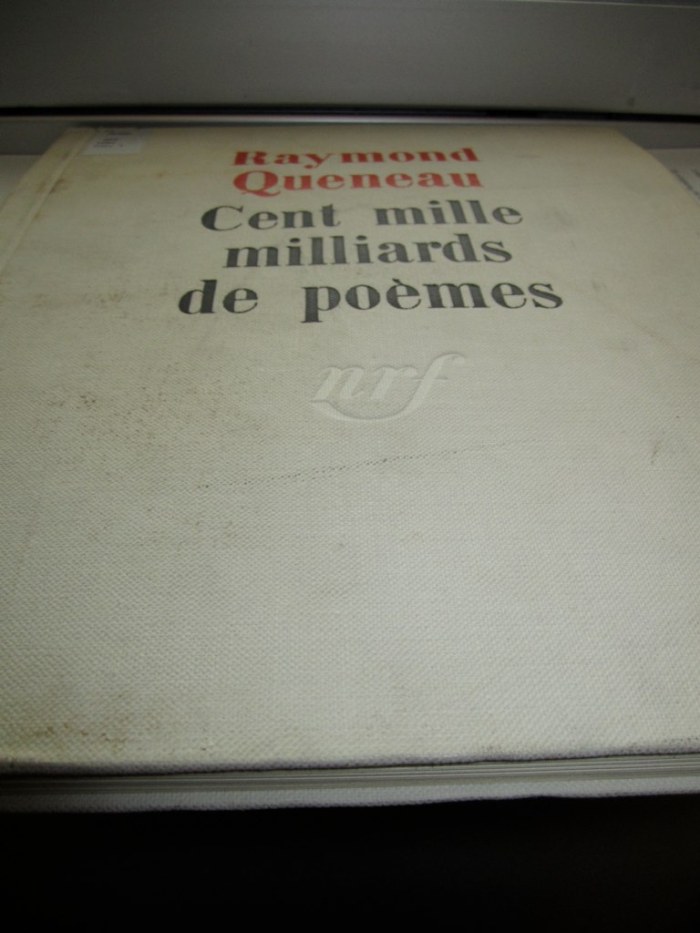

Cent mille milliards de poèmes

In English, the title translates to One hundred thousand billion poems, or else One hundred million million poems, or else One hundred trillion poems. The French have a crazy way of expressing numbers. (For instance, the series of quantities 4, 20, 9, 89, 10, 9, 19, 99, 96, 80, 16 would be said aloud as quatre, vingt, neuf, quatre-vingt-neuf, dix, neuf, dix-neuf, quatre-vingt-dix-neuf, quatre-vingt-seize, quatre-vingt, seize. Apparently with enough wine you can pronounce a hyphen.) In the case of this particular book, however, such combinatory flexibility is quite apt, for the author Raymond Queneau here proves his mastery at leveraging the power of recombination.

I don’t know much about poetry, but when I imagine a book of one hundred trillion poems, I imagine a very thick book. As we read in the postface by François Le Lionnais, who assisted Queneau, “The work you are holding in your hands represents, itself alone, a quantity of text far greater than everything man has written since the invention of writing, including popular novels, business letters, diplomatic correspondence, private mail, rough drafts thrown in the wastebasket, and graffiti.” In fact, at one poem per standard 20-pound sheet of paper, my calculations suggest the book would be approximately 6 million miles thick. (Thanks to the electronic god-brain Wolfram Alpha for confirming my math.) But no! Though rather wide and tall, Queneau’s book isn’t very thick at all:

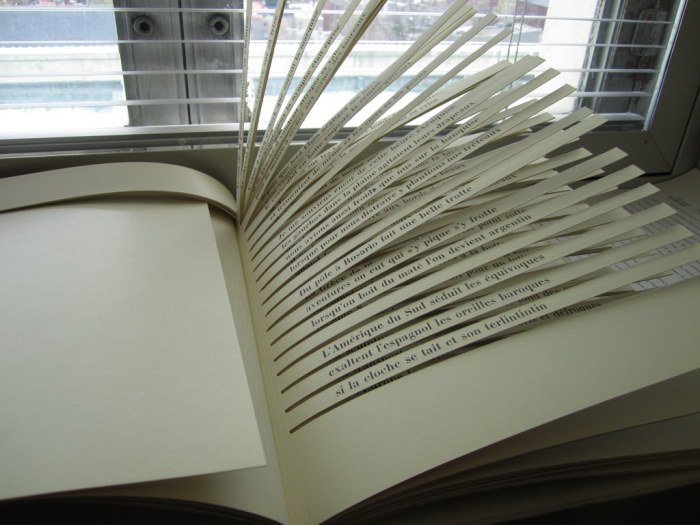

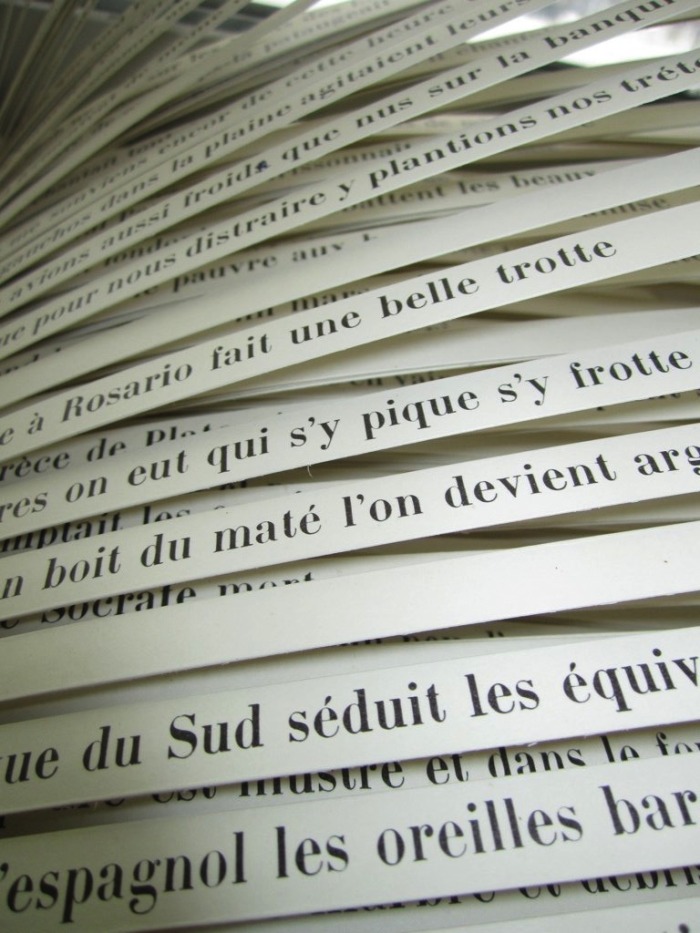

How, you ask, does the genius Queneau do it? The magic happens with ten sonnets and a pair of scissors. Each sonnet not only follows the same rhyme scheme, but bears the same rhyming sounds in the same places—so that one can replace, say, the final line of one poem with the final line of another, without breaking any formal rules. Cutting slits on either side of each line of each poem yields a fanfare of recombinable lines, easy to rearrange into one hundred trillion possible sonnets:

In his introductory “Mode d’emploi”—a term that would resonate through the OuLiPoan tradition that this book, in 1961, set rolling—Queneau says that his little book allows “everyone to compose” these trillions of sonnets, and that he hopes his little sonnet-machine will always produce poems with a formal and grammatical regularity, as well as “a theme and a continuity” to hold them together. There is a gratifying viscosity, a density in moving through this thicket of sonnet material—quite like getting chased by tigers through a bamboo forest:

As with so many strange books, this one proves difficult to handle. My fingers are so accustomed to the wholeness of the sheet, they become trembly and useless with these strips splaying themselves out everywhere. Happily, Gordon Dow has produced a more user-friendly online version of the original text, and Beverly Charles Rowe provides multiple digital versions in English. The internet seems as apt a destination as any for this strange book; scholars of new media writing have long seen Queneau’s many sonnets as a precursor to the textual combinatorics that hypertext and related technologies enable. (Indeed, Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort provide an extremely limited excerpt of Queneau’s book—percentage-wise, probably the smallest excerpt ever—in their wonderful The New Media Reader.) But when the day is done, there’s nothing quite like physically holding the uncanny slimness of this very big, very strange book. You can get such a “bookbound” copy here

.

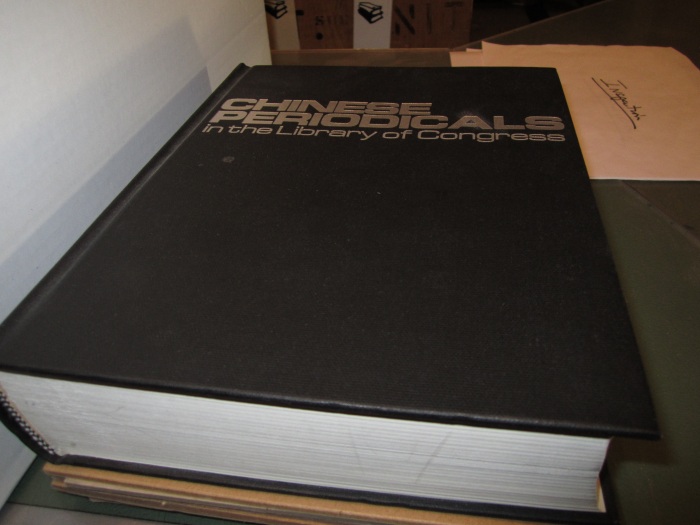

Chinese Periodicals in the Library of Congress: A Bibliography

I found a finding aid. But this book, for me, is all about its setting. I discovered it sitting on a counter-top some months ago, and there it has sat, all day, every day, since then. This is a huge book to leave lying around:

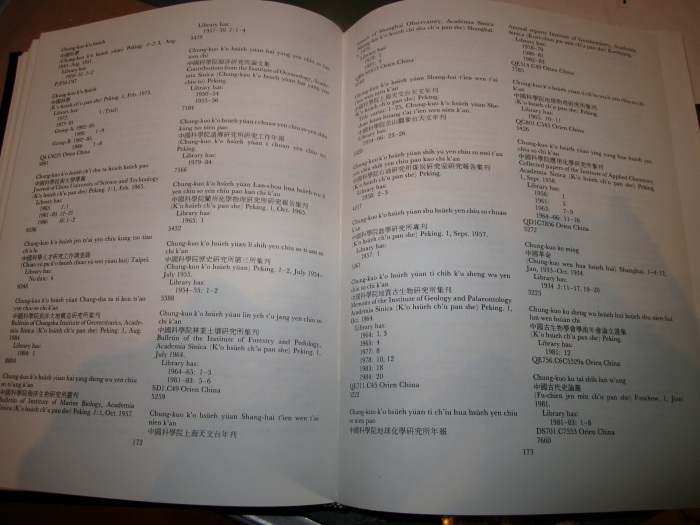

The counter-top in question is in the Library of Congress, at one end of a vast reading room now repurposed with cubicles for librarians to do their bibliological thang. The two compilers (as they call themselves on the cover page) are Han-Chu Huang and David H.G. Hsu, who brought out the book in 1988. In Huang’s case, the first hits on a Google search of his name refer to this very bibliography—but just looking at the thing, we don’t exactly need Google to recognize it as a substantial project. David H.G. Hsu, for his part, is not to be confused with the Wharton Business School professor by the same name. Different guy. Like so many of the strangest books, this one does what it promises. We get 814 carefully wrought pages of Chinese periodicals in the Library of Congress:

Given this book’s sheer inertia, I had thought it safe to assume it never got much play. After all, here it was: a book apparently produced by two employees of the Library of Congress, published with funding from the Library of Congress, whose sole purpose was to list certain holdings of the Library of Congress, sitting in perhaps the only room in the entire world where people might have regular occasion to use it—a room, that is, in the Library of Congress where other employees of the Library of Congress spend their days sorting and stacking and listing and distributing the holdings of the Library of Congress—and yet it had sat apparently untouched for weeks. One would have expected it to get passed around like the cup at a one-cup kegger. Imagine my delight, then, to see the Internet positively brimming with references to this reference. You can even buy onefor yourself, for not that much money, should you become so inclined.

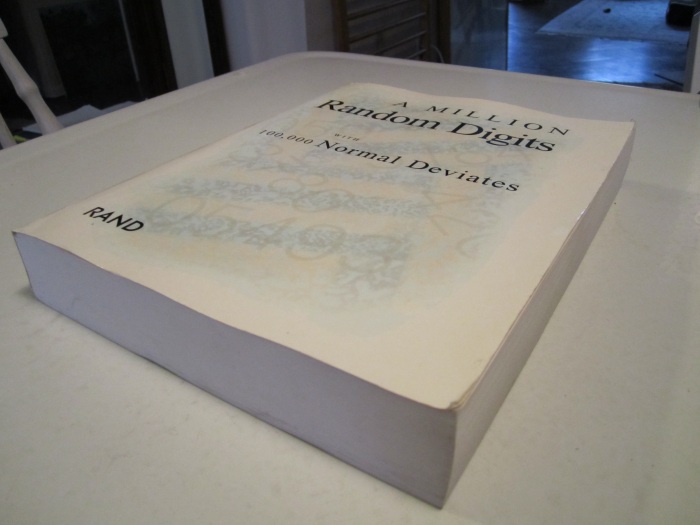

A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates

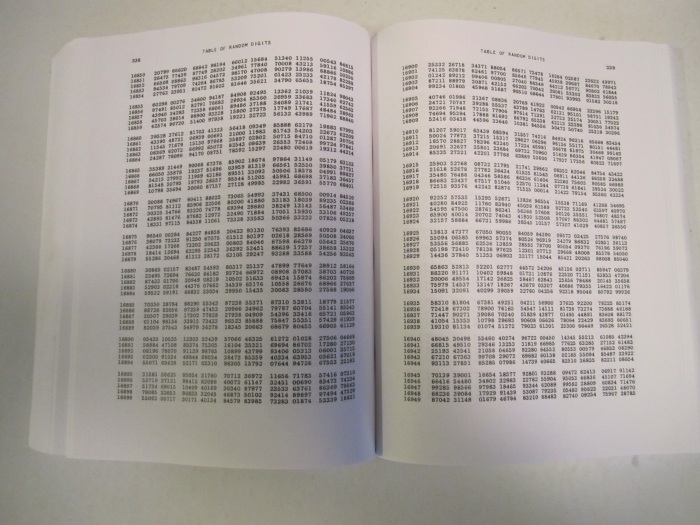

First published for the RAND Corporation in 1955 by the Free Press of Glencoe, Illinois, A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates contains exactly what you’d suspect: an extremely large table of random digits. One can hardly resist the impulse to open this hefty volume, but good luck actually reading it. Viz.:

Production of the so-called RAND Book began at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1947. Scientists there were developing a new branch of mathematics called the Monte Carlo Method, which uses random sampling to model complex systems. As it happened, the main complex system in need of modeling was the chaotic reaction inside the thermonuclear weapons that RAND scientists were then helping to design at Los Alamos. Of course, this is one of several important random number tables, but its connection with Cold-War weaponization is particularly interesting. Stanislaw Ulam is credited with the initial idea for Monte Carlo mathematics, and he developed it in collaboration with John von Neumann and the astoundingly named Nicholas Metropolis. Enrico Fermi had already used random sampling techniques in some of his experiments at the University of Chicago in the 1930s, but only in the late 1940s and 1950s at Los Alamos would they become formalized and see routine use. As the Introduction to the first edition puts it, “the applications required a large supply of random digits or normal deviates of high quality,” and the RAND Book was produced to answer this need. It was created using an electronic roulette wheel in conjunction with a random-frequency pulse. The random pulse likely was a gas noise tube, though as Tom Jennings’s wonderful reconstruction proves, a geiger counter trained on uranium ore would have worked equally well—while also lending the whole affair a delightful circularity. (Jennings has previously reviewed the first edition of the RAND Book.) Monte Carlo mathematics has since become important for complex systems theory, chaos math, environmental science, and a variety of other disciplines, and the RAND Book remains among the most trusted and widely used tables of random digits. A copy is now available online, but for those who prefer to feel this volume’s heft in their hot little hands, the RAND Corporation graciously issued a second edition in 2001, available on Amazon. The tables themselves remain unchanged, of course—in fact, like the first edition, they were not conventionally typeset but reproduced directly from computer printouts, by photo-offset, in order to avoid typographical errors. The new edition does, however, provide an updated Foreword in celebration of this very strange book. Also available is a thrilling sequel

by David Dubowski, who uses computer algorithms to provide an equally large table, now with more perfectly random distribution—whatever that means.