Archive for the ‘Poetry’ Category

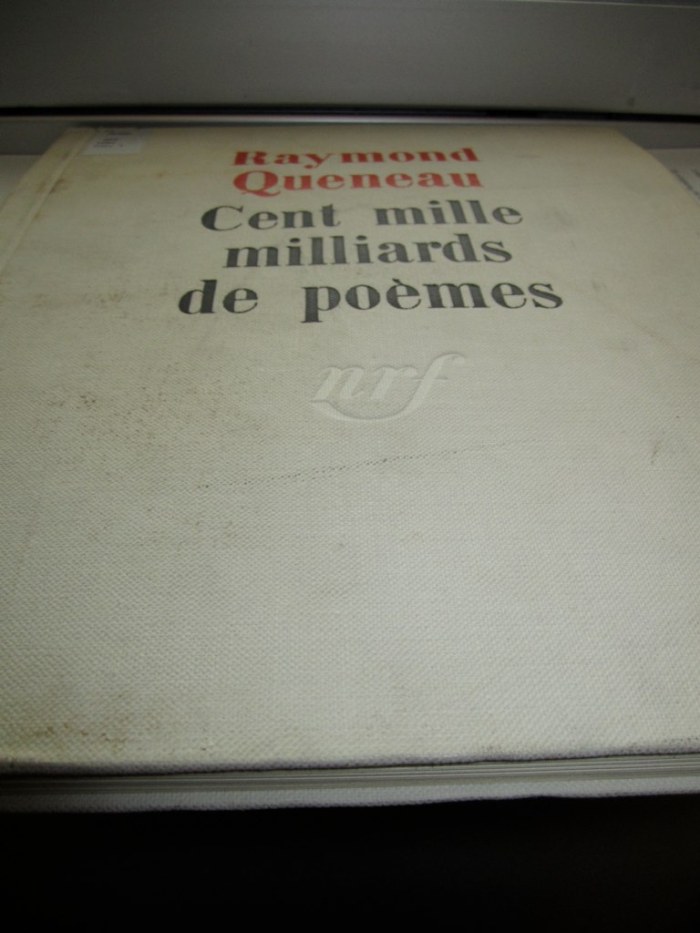

Cent mille milliards de poèmes

In English, the title translates to One hundred thousand billion poems, or else One hundred million million poems, or else One hundred trillion poems. The French have a crazy way of expressing numbers. (For instance, the series of quantities 4, 20, 9, 89, 10, 9, 19, 99, 96, 80, 16 would be said aloud as quatre, vingt, neuf, quatre-vingt-neuf, dix, neuf, dix-neuf, quatre-vingt-dix-neuf, quatre-vingt-seize, quatre-vingt, seize. Apparently with enough wine you can pronounce a hyphen.) In the case of this particular book, however, such combinatory flexibility is quite apt, for the author Raymond Queneau here proves his mastery at leveraging the power of recombination.

I don’t know much about poetry, but when I imagine a book of one hundred trillion poems, I imagine a very thick book. As we read in the postface by François Le Lionnais, who assisted Queneau, “The work you are holding in your hands represents, itself alone, a quantity of text far greater than everything man has written since the invention of writing, including popular novels, business letters, diplomatic correspondence, private mail, rough drafts thrown in the wastebasket, and graffiti.” In fact, at one poem per standard 20-pound sheet of paper, my calculations suggest the book would be approximately 6 million miles thick. (Thanks to the electronic god-brain Wolfram Alpha for confirming my math.) But no! Though rather wide and tall, Queneau’s book isn’t very thick at all:

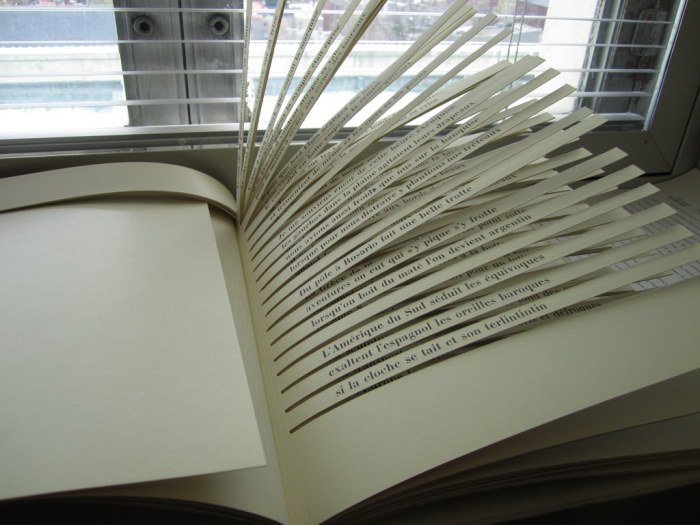

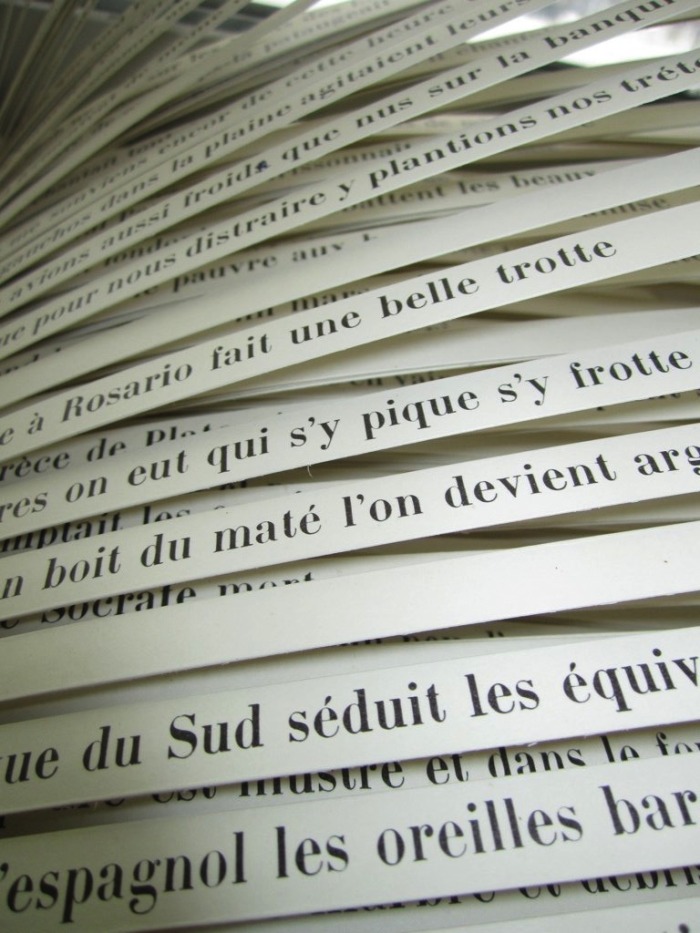

How, you ask, does the genius Queneau do it? The magic happens with ten sonnets and a pair of scissors. Each sonnet not only follows the same rhyme scheme, but bears the same rhyming sounds in the same places—so that one can replace, say, the final line of one poem with the final line of another, without breaking any formal rules. Cutting slits on either side of each line of each poem yields a fanfare of recombinable lines, easy to rearrange into one hundred trillion possible sonnets:

In his introductory “Mode d’emploi”—a term that would resonate through the OuLiPoan tradition that this book, in 1961, set rolling—Queneau says that his little book allows “everyone to compose” these trillions of sonnets, and that he hopes his little sonnet-machine will always produce poems with a formal and grammatical regularity, as well as “a theme and a continuity” to hold them together. There is a gratifying viscosity, a density in moving through this thicket of sonnet material—quite like getting chased by tigers through a bamboo forest:

As with so many strange books, this one proves difficult to handle. My fingers are so accustomed to the wholeness of the sheet, they become trembly and useless with these strips splaying themselves out everywhere. Happily, Gordon Dow has produced a more user-friendly online version of the original text, and Beverly Charles Rowe provides multiple digital versions in English. The internet seems as apt a destination as any for this strange book; scholars of new media writing have long seen Queneau’s many sonnets as a precursor to the textual combinatorics that hypertext and related technologies enable. (Indeed, Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort provide an extremely limited excerpt of Queneau’s book—percentage-wise, probably the smallest excerpt ever—in their wonderful The New Media Reader.) But when the day is done, there’s nothing quite like physically holding the uncanny slimness of this very big, very strange book. You can get such a “bookbound” copy here

.