Archive for the ‘Illegible Books’ Category

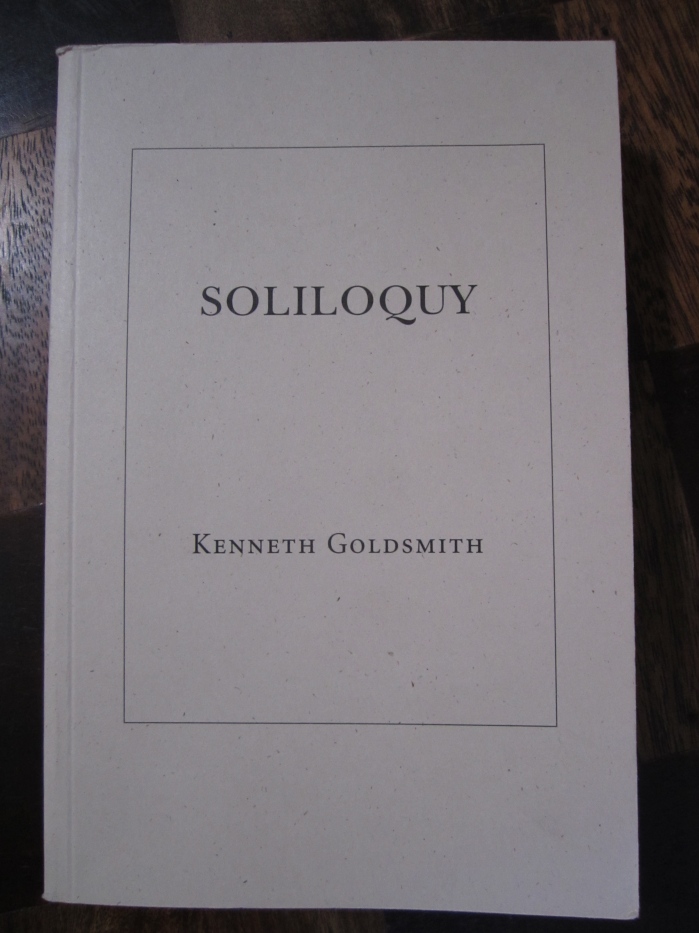

Soliloquy

Kenneth Goldsmith specializes in writing books so long and boring and excruciatingly attentive to minutiae that no one can be expected actually to read them. Consider Day (Figures, 2003), in which Goldsmith transcribes verbatim the contents of an entire single issue of The New York Times, including marginalia, bylines, captions, and even stock prices. This 840-page tome is so mind-numbingly large and mundane that even Goldsmith has purportedly confessed that, at a certain stage, he gave up on hand-keying the text and instead scanned pages and used text-recognition software to import it.

That such books have risen beyond mere cult curiosity and become fixtures of the American literary terrain—largely without even getting read—is either a testament to their quality or a telling indication of just where their strengths lie. And let’s be clear: Goldsmith has frequently stated that he actually wants his books to go unread, to be recognized far and wide as supremely unreadable. Such are the stakes of his project.

The books of his “American Trilogy” continue such excruciating attentions to language, as it exhaustively describes and thoroughly constructs our ambient environments: The Weather (Make Now, 2005) transcribes a full year of NYC-area televised weather reports; Traffic (Make Now, 2007) transcribes NYC traffic reports; and Sports (SPD, 2008) transcribes the full broadcast of the longest baseball game on record, a five-hour 2006 bout between the Yankees and the Red Sox. Just as, in this trilogy, Goldsmith’s idea of the “American” never strays far beyond Manhattan, so has his idea of poetic invention remained quite confined to the “uncreative” processes of transcription and recording that he considers a radical departure from the implicitly conservative eddies of traditionally expressive writing. If his experiments thus miraculously help us to escape the shackles of crypto-fascist humanisms, we pay our way in boredom—and even, at times, by sacrificing the very act of reading itself. Who wants to write a new poem, a new novel, when the real space for invention lies in regurgitating the language already floating around us? And by the same token, who wants to read such regurgitated language, when we could be watching The Office instead? In the moment after my jaw drops at how clever Goldsmith really is, I find myself fighting the urge to take my ball and go home.

As its title suggests, Soliloquy (Granary, 2001) helps me to work through this sense, when considering Goldsmith’s work, that perhaps, as Larkin put it, “books are a load of crap.” Weighing in at 296 pages and 1.4 pounds, this volume provides a transcription of every word uttered by the author during a one-week period. He kept a voice recorder on his person during this time and subsequently transcribed the results. Take one look at the book, and you’ll see that the transcription alone must have been an heroic undertaking—though again, if we wanted a sense of just how hard great writers work, we already had Flaubert and Tolstoy (and Tolstoy’s wife, who lacked the luxury of a QWERTY keyboard when she transcribed hubby’s massive manuscripts, over and over again). These scribblers were kind enough to leave us with texts not only difficult to produce but potentially enjoyable to read. If Flaubert was a bourgeois apologist, then Goldsmith may be an apologist for not reading books at all. Works like Soliloquy overwhelm, but perhaps not intellectually. They overwhelm physically, visually. They force us to ask how we could—who possibly could—have time to read his work. And what can it mean to take a book seriously, if not to read it?

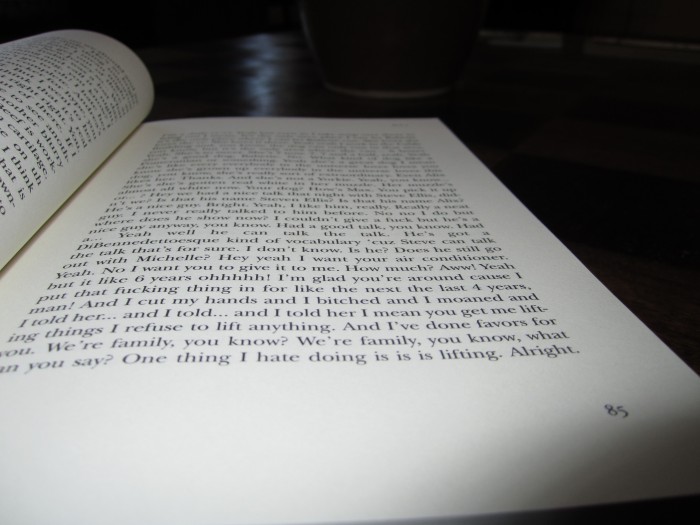

Goldsmith tells us that he transcribed the recordings of Soliloquy during eight-hour days as a writing resident at some fancy French retreat. He also tells us that Soliloquy is an “unedited document,” despite his apparently having decided not to transcribe a single word of the many interlocutors with whom he spoke during the recording process—interlocutors whose voices presumably, in some cases at least, also registered on the microphone. Far from getting the intimate sense of language’s daily textures that the project seems to promise, the book instead provides us with an extended experiment in hearing only half of a conversation. It is like that annoying experience of overhearing some stranger on the telephone—say, while you’re in the airport or on a bus.

After reading a little of this, I decided to ruin the story for myself by skipping to the end. The very last page of Soliloquy offers a Postscript, a maxim Goldsmith has often repeated elsewhere: “If every word spoken in New York City daily were somehow to materialize as a snowflake, each day there would be a blizzard.” Dear readers, this simply is not the case. There is wide variation among estimates of how many words people speak per day, but 20,000 per day is among the higher figures. Let’s generously assume that New Yorkers speak twice as much as average mortals, so that’s 40,000 words per day. Let’s look only at the island of Manhattan, the city’s most densely populated area. Even more generously, let’s take Manhattan’s daytime population rather than the number of actual residents: that’s 2.87 million people, which we’ll round to 3 million. Multiply 3 million by 40,000 words per day, and you get 120 billion words. That is, by any account, a lot of words. But what if they were snowflakes? The total land area of Manhattan—again, generously, ruling out bodies of water—is 59.5 square kilometers, which we can round to 60 square km, which is equal to 60 million square meters. A little division—120 billion over 60 million—and you get a paltry 2,000 snowflakes per square meter. Now, I can’t find figures on the average number of snowflakes per cubic centimeter—and likely that figure varies wildly—but I can confidently say that 2,000 flakes distributed over a square meter of ground is not a blizzard. That’s not even a healthy dusting. For those following at home, we’re talking about 0.2 snowflakes per square centimeter. The Postscript to Soliloquy, like the book itself and so much of Goldsmith’s other work, ultimately bespeaks a powerful attraction to the idea of great quantity but not to its actuality, for the actualities of scale in our lived worlds do not always align as interestingly with our ideas of scale as one might hope. In other words, the verbal blizzard is like Soliloquy itself: the idea of it is rather lovely. But its virtues may stop there, if we still live in a world where books are for reading—and, one hopes, for enjoying. And where the most troubling kinds of weather lately seem to be those that leave snowflakes a bit too thin on the ground.

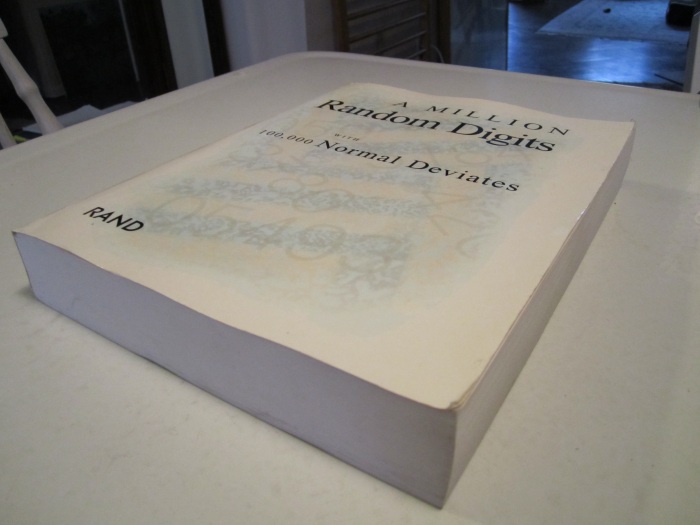

A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates

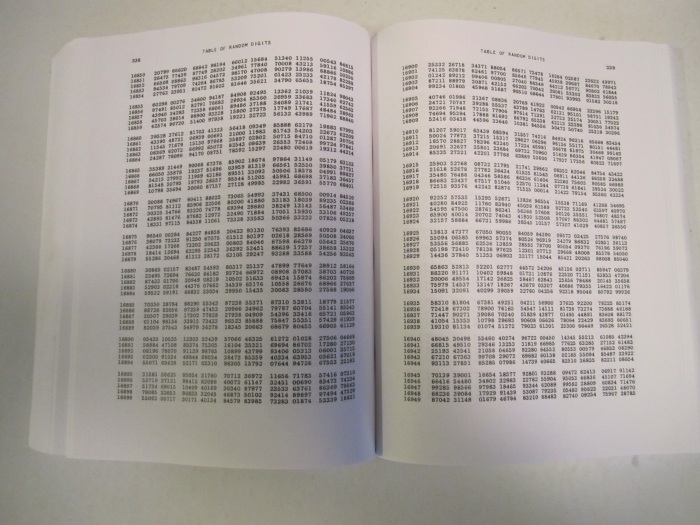

First published for the RAND Corporation in 1955 by the Free Press of Glencoe, Illinois, A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates contains exactly what you’d suspect: an extremely large table of random digits. One can hardly resist the impulse to open this hefty volume, but good luck actually reading it. Viz.:

Production of the so-called RAND Book began at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1947. Scientists there were developing a new branch of mathematics called the Monte Carlo Method, which uses random sampling to model complex systems. As it happened, the main complex system in need of modeling was the chaotic reaction inside the thermonuclear weapons that RAND scientists were then helping to design at Los Alamos. Of course, this is one of several important random number tables, but its connection with Cold-War weaponization is particularly interesting. Stanislaw Ulam is credited with the initial idea for Monte Carlo mathematics, and he developed it in collaboration with John von Neumann and the astoundingly named Nicholas Metropolis. Enrico Fermi had already used random sampling techniques in some of his experiments at the University of Chicago in the 1930s, but only in the late 1940s and 1950s at Los Alamos would they become formalized and see routine use. As the Introduction to the first edition puts it, “the applications required a large supply of random digits or normal deviates of high quality,” and the RAND Book was produced to answer this need. It was created using an electronic roulette wheel in conjunction with a random-frequency pulse. The random pulse likely was a gas noise tube, though as Tom Jennings’s wonderful reconstruction proves, a geiger counter trained on uranium ore would have worked equally well—while also lending the whole affair a delightful circularity. (Jennings has previously reviewed the first edition of the RAND Book.) Monte Carlo mathematics has since become important for complex systems theory, chaos math, environmental science, and a variety of other disciplines, and the RAND Book remains among the most trusted and widely used tables of random digits. A copy is now available online, but for those who prefer to feel this volume’s heft in their hot little hands, the RAND Corporation graciously issued a second edition in 2001, available on Amazon. The tables themselves remain unchanged, of course—in fact, like the first edition, they were not conventionally typeset but reproduced directly from computer printouts, by photo-offset, in order to avoid typographical errors. The new edition does, however, provide an updated Foreword in celebration of this very strange book. Also available is a thrilling sequel

by David Dubowski, who uses computer algorithms to provide an equally large table, now with more perfectly random distribution—whatever that means.