Archive for the ‘Books about Books’ Category

A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel

It is a thing uncommonly strange to see a book appear at the physical expense of another book, but here we have it. British artist Tom Philips published his “treated” novel, A Humument, in 1970 to much art-world fanfare and delighted chin-scratching. Philips had begun the project some years earlier, when he sauntered into a bookstore and selected “by chance” a book that he would then alter (read: enhance? mutilate? transform? plagiarize? appropriate?) to make his own work. The book Philips selected was A Human Document, a supposedly “forgotten” 1892 novel by the wonderful and multi-talented Oxford man, William Hurrell Mallock. It remains rather a mystery to me why Mallock has come in for so much rough treatment this past half-century. Perhaps it’s because his economic writings are anti-socialist in a way that, these days, has become quite more than gauche. Whatever the man’s political leanings, A Human Document seems rather a delightful novel for a rainy Sunday afternoon, well worth the read in chortles and ah-has.

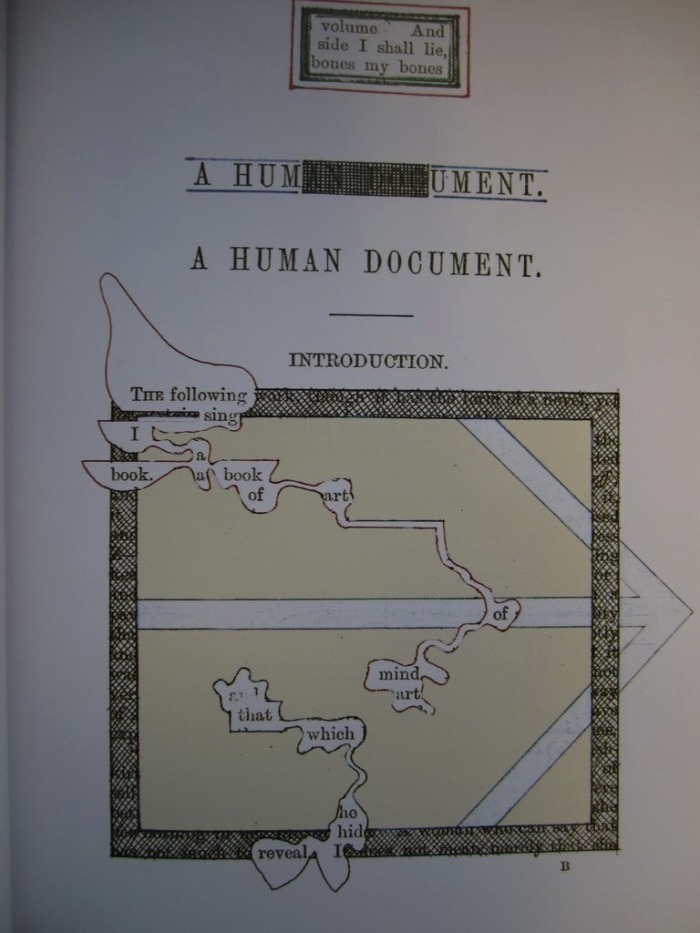

Mallock’s novel is not, in and of itself, a particularly strange book. Well, that all changed when Philips got his hands on it. As you can already see in the “treated” version of the opening page, Philips’s strategy is to make all sorts of strategic colorful doodles over Mallock’s carefully wrought verbiage, in order to construct a “new” work, the title of which emerges through partial erasure and conflation: A Human Document.

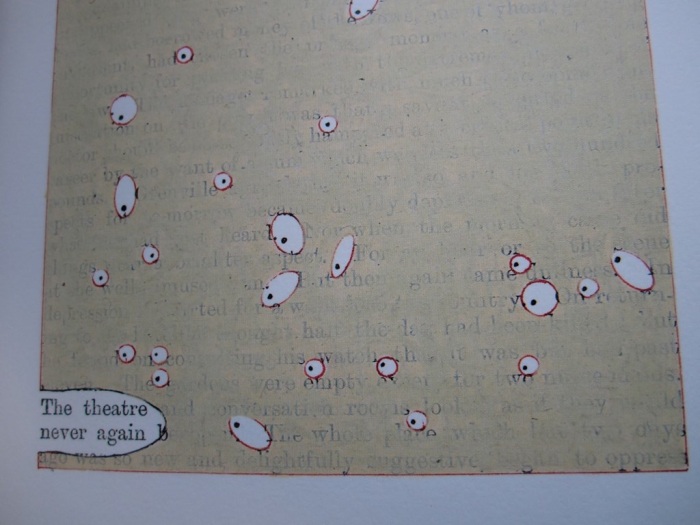

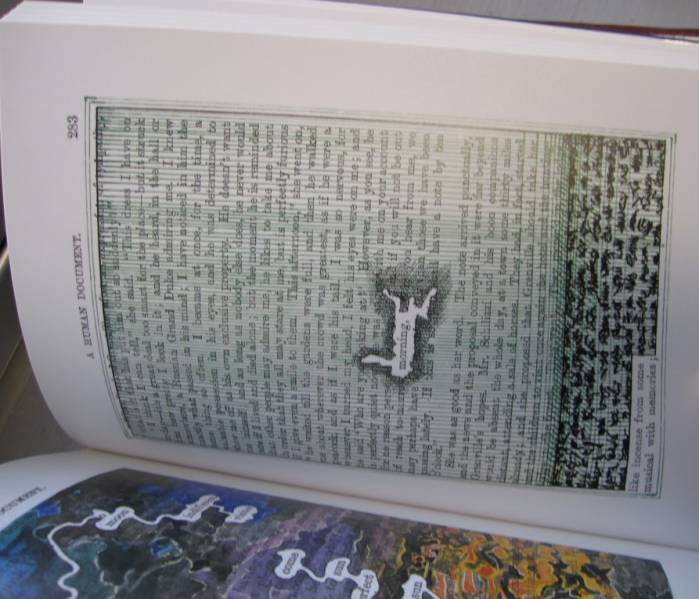

The transformed work purportedly tells the story of one Bill Toge—a character not evident in Mallock’s writing. But the true pleasure of the book, if you take it at all, lies in the stunning visual textures Philips deploys throughout. After all, we can safely suppose that had Philips wished simply to tell a story about a character he’d invented, this Bill Toge, he might have turned to blank paper and the not insignificant resources of his own imagination. But no, Philips is a visual artist, and his project for A Humument has always been primarily visual.

As someone interested in strange books—and only secondarily in, say, strange doodles—I can hardly help but wonder what it would mean to produce a “treated” version of A Humument itself. I find myself tempted to transcribe with loving care each of Mallock’s words that Philips left visible, peeking through his designs, and to typeset them in the most visually plain, regular fashion of prose that our technology can muster.

In the meantime, A Humument is available for purchase in book form, and Philips also has created a Web site for A Humument, where you can “read” the full text online and even download the iPad app.

Chinese Periodicals in the Library of Congress: A Bibliography

I found a finding aid. But this book, for me, is all about its setting. I discovered it sitting on a counter-top some months ago, and there it has sat, all day, every day, since then. This is a huge book to leave lying around:

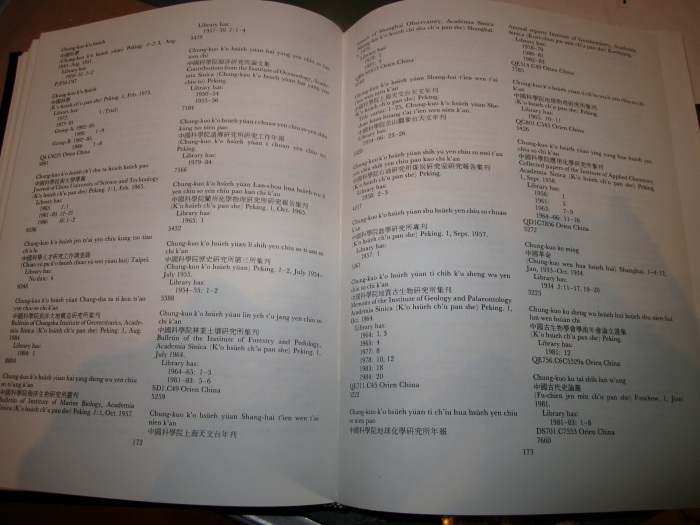

The counter-top in question is in the Library of Congress, at one end of a vast reading room now repurposed with cubicles for librarians to do their bibliological thang. The two compilers (as they call themselves on the cover page) are Han-Chu Huang and David H.G. Hsu, who brought out the book in 1988. In Huang’s case, the first hits on a Google search of his name refer to this very bibliography—but just looking at the thing, we don’t exactly need Google to recognize it as a substantial project. David H.G. Hsu, for his part, is not to be confused with the Wharton Business School professor by the same name. Different guy. Like so many of the strangest books, this one does what it promises. We get 814 carefully wrought pages of Chinese periodicals in the Library of Congress:

Given this book’s sheer inertia, I had thought it safe to assume it never got much play. After all, here it was: a book apparently produced by two employees of the Library of Congress, published with funding from the Library of Congress, whose sole purpose was to list certain holdings of the Library of Congress, sitting in perhaps the only room in the entire world where people might have regular occasion to use it—a room, that is, in the Library of Congress where other employees of the Library of Congress spend their days sorting and stacking and listing and distributing the holdings of the Library of Congress—and yet it had sat apparently untouched for weeks. One would have expected it to get passed around like the cup at a one-cup kegger. Imagine my delight, then, to see the Internet positively brimming with references to this reference. You can even buy onefor yourself, for not that much money, should you become so inclined.